PostWar Japan: 1945–1951

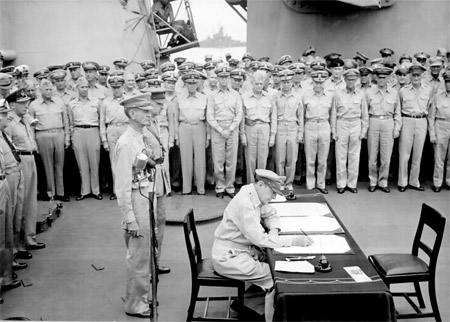

General Douglas MacArthur signs as Supreme Allied Commander during formal surrender ceremonies on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945. Behind General MacArthur are Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright and Lieutenant General A. E. Percival. [LISTEN]

As presiding officer at the ceremony, MacArthur made the following statement:

“Today the guns are silent. A great tragedy has ended. A great victory has been won. The skies no longer rain death – the seas bear only commerce – men everywhere walk upright in the sunlight. The entire world is quietly at peace. The holy mission has been accomplished.”

MacArthur provided insight on what he hoped to accomplish in Japan when he stated that day:

“Men since the beginning of time have sought peace, but military alliances, balances of power, leagues of nations, all in turn failed, leaving the only path to be by way of the crucible of war.”

MacArthur, in his unarmed aircraft The Bataan, had landed several days earlier at Atsugi Airfield near Tokyo to take up his duties as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. Following the formal surrender on the Missouri, MacArthur proceeded with the fulfillment of his vision, which would leave a lasting impact on Japan and the world.

MacArthur found in Japan a country that was devastated and whose population was close to starvation. Fifteen million Japanese were homeless and another six million disarmed soldiers and civilians were about to return from areas throughout the Pacific region.

Many leaders of the Allied Powers favored retribution, including putting Emperor Hirohito on trial as a war criminal, but MacArthur had studied the history of previous conquerors including

Hundreds of F4U Corsairs and F6U Hellcats fly in victory formations over the surrender ceremonies in Tokyo Bay, Japan. The USS Missouri (front left) is anchored along with other U.S. and British ships.

Alexander, Napoleon and Hitler and he knew that their occupations had all ended in failure. He had observed and embraced the Asian culture during his earlier years in the Philippines and he had started the transition to democracy in the Philippines after the liberation of the islands. Rather than punishing Emperor Hirohito, MacArthur utilized him to help fulfill his vision of democracy for Japan.

Under chaotic and potentially explosive conditions, MacArthur remained calm and confident in his decisions. He managed to feed people who were close to starvation while steps were taken to avoid humiliation and disrespect of the Japanese people. The Emperor was allowed to reign in a symbolic capacity to give the Japanese people emotional and structural continuity. War criminals, however, were tried and some were executed.

Wartime political leaders were removed from power and the Japanese educational system was modified. MacArthur consistently rejected attempts to punish the Japanese people and the process of change evolved without civil or guerrilla warfare. In October 1945, MacArthur issued the Civil Liberties Directive abolishing practices and laws that infringed upon political, civil and religious rights and eliminating military control by the government. Japanese military and civil officials responsible for promoting war were banned from further service.

At the same time, representatives of the allied powers gained a degree of control over the constitution-building process with the formation of the Far Eastern Advisory Commission. In December of 1945 U.S. Secretary of State James Byrnes sent recommendations that became the basis for U.S. policies concerning governmental and constitutional reform in Japan.

Outside pressure had been building to conduct the Japanese occupation in a different manner. The Russians sought to occupy Hokkaido, the northern island of Japan, and – joined by the British – intensified pressure for a division of the power of MacArthur. Without the knowledge of MacArthur, Secretary of State Byrnes met in Moscow with representatives of Russia and Britain to discuss new spheres of allied responsibility in Japan.

Tokyo in the aftermath of war. The devastating firebombing on the night of 910 March,1945, killed about 88,000 to 125,000 civilians, creating more devastation than the U.S. deployment of atomic weapons inflicted on either Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

MacArthur, despite his massive responsibilities in Japan, was also carefully following and evaluating the post-war situation in Germany. In his book Reminiscences, MacArthur said he had concluded that establishing separate zones of occupation had been a serious mistake. MacArthur refused to allow it in Japan. When Russian General Derevyanko pressed the point, MacArthur turned him down “point blank.” Derevyanko became “almost abusive” and threatened to have MacArthur removed as Supreme Commander.

It was clear that MacArthur, although under both domestic and international pressure, intended to pursue his own approach in Japan. He was confident that his plan, over time, would be more effective than the policies of division in Europe.

MacArthur, ignoring outside pressures, directed Japanese officials to recommend revisions to the 1889 Meiji Constitution. The Japanese government created the Constitutional Problem Investigation Committee. The Committee, after several weeks of deliberation, submitted recommendations intended to restore and preserve what was left of the old order. MacArthur rejected these changes as being nothing more than a rewording of the Meiji Constitution.

Anxious to move the constitutional process forward, MacArthur, in February 1946, instructed General Courtney Whitney to develop a new draft constitution as an amendment to the Meiji Constitution. MacArthur specified that the new constitution must include limited monarchy, renunciation of war, and the abolition of feudalism. He added requirements of human rights, women’s rights, the rights of unions, and basic freedoms including free speech and freedom of the press as the document developed.

Following the first meeting of the Whitney team – which included Whitney, Col. Charles L. Kades, Lt. Col. Milo E. Rowell, and Commander Alfred R. Hussey along with Japanese officials including Foreign Minister Yoshida Shigeru, Matsumoto Joji, -Shirasu Jiro, and Hasegawa Motokichi – the drafting and approval process continued for fifteen months.

Japanese-American author Koyoto Inoue characterized the new Constitution in the title of her scholarly book: MacArthur’s Japanese Constitution. The book offers vivid insight into how the Japanese were able to address cross-cultural and cross-linguistic factors in fashioning a document which advanced combined Japanese and American values to create a new political system. The numerous drafting and approval processes required extensive participation and the ultimate approval of Japanese officials and entities. There were multiple meetings of the Japanese Cabinet, the Cabinet Bureau of Legislation, the Association for the People’s National Language Movement, the Privy Council (11 meetings), the National Diet (114 days of debate), the House of Representatives (HOR) Special Committee (meetings spanning 24 days), the House of Peers (HOP) Special Committee (16 sessions) and its subcommittee (4 days in closed session). Despite constant outside pressure to alter and influence this process, MacArthur remained firm in his commitment to a democratic government for Japan. Japanese officials and the Japanese people eventually embraced his vision.

General MacArthur and Emperor Hirohito at their first meeting. They spoke for forty minutes but the content of their conversation has never been made public.

On August 24, 1946, the HOR voted approval 429 to 8 and on October 6, 2023 the HOP passed the new Constitution with over a two-thirds majority. A few amendments were worked out and finalized thereafter the new Constitution was promulgated on November 3, 1946. It went into effect six months later, on May 3, 1947, which subsequently became a national holiday in Japan – Constitutional Memorial Day.

MacArthur also influenced Japanese leadership to implement additional reforms involving land ownership, education and decentralization of the economy. Japan would no longer be controlled by a small group of powerful land owners and businessmen. MacArthur, in his Reminiscences, was generous in sharing credit for this historic accomplishment:

“In these various reforms, numerous officials of the occupation distinguished themselves – Whitney, Marquat, Willoughby, Sams, Dodge, Moss, Schenk, Shoup, Kades and many others. Without their special talents and skill, little would have been accomplished. And the Japanese themselves truly earned the respect and faith of men of good will everywhere. Under their able prime minister Yoshida they rose, in their own merit, from the ashes of destruction to a vibrant nation firmly rooted in immutable concepts of political morality, economic freedom, and social privilege evolved from a blend of ideas and ideals of the west and their own hallowed traditions and time-honored cultures.”

MacArthur as Supreme Commander oversaw the implementation of many of the policies that had been approved by the Japanese themselves. From an historic standpoint the occupation was an enormous success, and MacArthur was seen in Japan as a fatherly – almost messianic – figure whose true concern was the well-being of the Japanese people.

MacArthur also was fortunate that Europe had been the primary focus of the Allied Powers. The fact that Asia had not been given a higher priority in World War II provided him a relatively unchallenged opportunity to implement his plan in Japan, but when he wanted similar powers five years later in Korea, he was rebuffed and removed from command. MacArthur’s leadership qualities, which were so successful during the War in the Pacific and the occupation of Japan – would be viewed differently during the Korean War.